A Note to the Reader

Normally I keep my private detective cases confidential. This one is an exception. But The Atlas Pursuit is more than just a detective story … you get to solve this mystery yourself.

You’re going to have to travel to places in New York City to figure everything out. Make sure to bring an internet-connected device with you — a smartphone at least, a tablet or laptop even better.

Also, please don’t be that guy. The Atlas Pursuit has a lot for you to figure out for yourself. Feel free to work with other people to solve it all. But once you figure things out, please keep everything to yourself. Please don’t tell your friends the answers, or post solutions on Facebook or Twitter, or upload pictures and clues on Instagram or your blog. That would ruin other people’s chance to solve it for themselves.

– David Wise

Part I

~1~

It sounds like the beginning of a Dashiell Hammett novel — my phone rang and on the other end was a Hollywood bombshell who needed my help solving a mystery involving her famous writer husband. Granted, she was a few decades past her prime. But in her day Patricia Neal was one of the hottest actresses on the silver screen. So you can imagine my surprise when she called, looking for my help. I’ll admit I was starstruck, and more than a little curious why she was calling. I found out when she arrived at my apartment later that day with a battered wooden box and one helluva story.

~2~

I guess you could call me a private detective, but not in the traditional sense. I don’t go chasing after philandering husbands or missing relatives.

My specialty is unusual.

This case started with that phone call back in the spring of 2009. It was a Friday morning, and I hadn’t left yet for my paper-pushing job at a Midtown office building. That job had nothing to do with my private eye work, but it was consistent and paid the bills in a way my detective work didn’t.

I was in my spare Upper East Side apartment, so far east it was practically in the river. It was unusual for my phone to ring so early in the morning. The voice on the other end was breathless and nervous.

“May I speak with David Wise please?”

“This is David.”

“Mr. Wise, my name is Patricia Neal.”

“Oh, like the actress?”

“Exactly like the actress. That is me. I am her.”

I was kidding. I didn’t expect that the Patricia Neal was calling. But then I connected the gravelly voice on the line with those old movies, like Hud and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and I realized that it was, in fact, her.

Patricia Neal, back in the day

“What can I do for you, Ms. Neal?”

“I understand you are something of an expert on New York mysteries, and codes, and things of that sort.”

“I guess you could say that.”

“I have something I want to show you, but it requires absolute discretion.”

“Discretion is my specialty.” I take my clients’ trust seriously. No trust, no clients. Almost all of my cases are strictly confidential. Most of my clients find me through the Central Park Papers, since that is semi-public. The rest get to me by referral. “What is it you have to show me?”

“I’d like to show you in person. Are you available?”

“I can certainly arrange to be.” Nothing I had planned, including that paper-pushing job, couldn’t be put aside for this. “When were you thinking?”

“Are you free now?”

“I guess I could make that work.”

“Can we meet at your place? Is it private?”

“It is. I mean, I live alone, but my apartment is small. Wouldn’t you prefer a coffeeshop or something?” It was true that I lived alone, but my boyfriend had stayed over the night before and was asleep in the bedroom. He slept right through the phone call.

“Mr. Wise, perhaps I haven’t impressed upon you how important the privacy of this is to me. I’m sure your apartment will be fine.”

“Okay. Privacy. Got it.” I gave her my address. By some coincidence, we only lived a few blocks away from each other, though those were the blocks that separated the movie stars from the hoi polloi. I called out of work with an imaginary cold that fooled no one. I woke my boyfriend and chased him out of the apartment with no explanation. He was confused, but obliged. Then I set to cleaning my apartment as fast as I could.

It’s probably best that I didn’t have too much time to worry about my clothes. What do you wear when a movie star is coming to your apartment? I decided neutral was best — a button down blue shirt and tan chinos. I was aiming for something professional and trustworthy but not too formal.

I also read up a bit about Patricia Neal online. Not many men in their 30s would have already known even a little bit about Patricia Neal. All the times as a kid that I stayed inside watching old movies instead of playing outside was finally paying off. I knew she was a famous, Oscar-winning actress, and somewhere in the back of my mind recalled hearing about a miraculous comeback from an almost-fatal stroke in the middle of her career. I didn’t know about her love affair with Gary Cooper, or that she was married to Roald Dahl, the famous writer of children’s books. But that’s about the extent of what I was able to find out before my buzzer rang.

~3~

I pressed the button to let her in. I did a last sweep of the apartment making sure I had shoved all of the dirty clothes and piles of papers into the closet. I did one final wipe down of my tiny table and even tinier counter. A while passed and there was still no knock on the door. Then the buzzer rang again.

“Come on in,” I said over the intercom.

“You didn’t tell me about the stairs,” the gravelly voice replied. “I don’t think I can make it up.”

“I’ll be right down.” I ran down the stairs — just a couple of flights, but with no elevator as an alternative. At the bottom of the stairs was a slightly hunched older woman. One hand held a cane, and the other a rolling suitcase.

“You didn’t tell me there was no elevator.”

“I’m sorry, Ms. Neal. Are you sure we can’t talk somewhere else?”

“No. I live close by and I can’t risk being seen. I’ll make it up the stairs, but I may need your help.”

“Of course. Why don’t I take your bag up, and then I’ll come back and help you.”

“I’m not letting this suitcase out of my sight for a minute, Mr. Wise. All three of us — you, me, and this bag — are going up these stairs together.”

She took hold of the banister with one hand and my arm with the other. I carried the suitcase and her cane with my free hand. It took a little while and a lot of effort, but finally, out of breath, she was seated at my little table. A few minutes and a glass of water later, she was ready to talk.

![By User:DavidShankbone (original), cropped and altered by Frauleinwunder [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://theatlaspursuit.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Patricia_Neal_2007-1008x1024.jpg)

Patricia Neal, around when we met

Handsome, I guess, is the best way to describe her. I could tell from her sharp features that in her day she was quite striking. She showed almost no symptoms from the stroke that 40 years earlier had left her speechless and immobile. Despite having left the South long ago, she still had the strange mix of formality and what my people would call chutzpah, though I imagine her people would call it gumption.

She was smartly dressed in a light purple blazer and black slacks. She moved and talked slowly, but mentally she was sharp. She reminded me of my grandmother. I had always chalked up my grandmother’s demeanor and directness to being a Brooklyn Jew, but evidently these qualities are more universal. The similarities between my guest and my grandmother put me at ease. But this was a miscalculation on my part, because my grandmother is always happy to see me. Ms. Neal disliked me from the minute she stepped into my apartment.

That’s not quite accurate. She just didn’t know if she could trust me, and she was brutally frank about it. “I don’t know if I can trust you” were practically the first words she said to me. “I don’t know who I can trust with this. I wish I didn’t have to trust anybody, that I could do it all myself, but I can’t.”

“I don’t even know what we’re talking about,” I said. “So why don’t you just tell me about it?” I had said the wrong thing.

“This is what I was afraid of. Anyone who helps me with this is going to try to take it away from me. The government is trying to get their hands on this right now. And they’re probably not the only ones. But it is mine. It belongs to me, and they’re not going to take it away from me and neither are you.”

“But,” I said, “you obviously came to me for a reason, and if you’re not going to tell me the reason, how can I help you?”

She calmed down a bit. “Let’s start again,” she said. “Thank you for letting me come to your apartment, Mr. Wise.”

“I’m sorry it’s not fancier. I’m sure you are accustomed to far less humble living.”

She laughed, saying, “You have me pegged all wrong, Mr. Wise. I’ve spent many years living in a convent, in a room far more humble than this.” With more time, I would have done more thorough research and known this.

“Mr. Wise, I’m sure you are curious why I’m here.”

“That’s an understatement.”

“It’s about a wedding present I recently rediscovered after many years of assuming it was lost. Actually, I didn’t think it was lost, so much as I thought that Roald had done something with it without telling me. I was married to Roald Dahl, the author.”

“That much I know.”

“We divorced a long time ago. But I recently received a letter from a bank, saying that the branch was closing and that my safe deposit box would need to be relocated. I vaguely remembered purchasing a safe deposit box around when Roald and I were married, though I really hadn’t thought about it since then. But the safe deposit box was in my name, and Roald has been dead for a number of years.

“You should know, Mr. Wise, that I am not a pack-rat. I was never one of those actresses who held on to all of her Hollywood momentos. But like everyone, I have a junk drawer, and inside was a key. For the longest time I couldn’t remember what that key opened. When I received the letter about the safe deposit box, I thought maybe that’s it. So I took the key and went to the bank. And sure enough.

“There wasn’t much in the box — some cash, an old savings bond that had long-since stopped accruing interest, and a couple of beaten-up wooden boxes.”

I couldn’t help but glance at the battered suitcase I had just carried up to my apartment. Were the contents of the safe deposit box inside?

Ms. Neal continued. “I knew those wooden boxes immediately. Not long after Roald and I were married, an old friend of his came to our apartment. He had been invited to the wedding, but he wasn’t able to make it, so he came for dinner after we got back from our honeymoon. This was back in 1953. I had never met the man before. To say that he was a friend of Roald’s might be an overstatement because, for as much respect as people had for him, not many people would refer to him as a friend. I had actually never heard Roald mention his name until we were putting together our wedding invitation list. There was almost no one Roald insisted on inviting, but this man I didn’t know was one of them. When I asked Roald why, he explained that William Stephenson was the man who recruited him into working on the war effort in America.”

I stopped her. “Do you mean William Stephenson, as in the William Stephenson. As in The Man Called Intrepid?”

“You’ve heard of him?”

I certainly had. All those things that made me a peculiar kid, like being a history buff, were now coming in handy as a historical sleuth. Much has been written about William Stephenson, including the claim that his efforts shortened World War II by years. Stephenson had almost single-handedly brought intelligence work to the U.S. as the head of an organization called British Security Coordination (BSC). That organization was a precursor of sorts to the CIA. I told Patricia Neal all of this.

“Well you know more about him than I did when Roald mentioned him. I asked Roald why he had never mentioned Bill before, if they were so close. Roald said that their relationship was not ‘close’ per se, and at the end of the war they had a falling out.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Roald wasn’t entirely forthcoming, but he said he felt that Bill hadn’t told him everything that happened during the war. This was a problem for Roald, since Bill had asked Roald to write the history of everything BSC had done. If Bill wasn’t going to be fully honest with him, how could Roald complete the project? So he bowed out. Roald never lost respect for Bill, but this put a damper on their relationship that lasted until that night when Bill came to our apartment for dinner with the most unusual wedding present ever given.

“I was 27, and newly married. Hollywood hadn’t exactly prepared me for the job of housewife. And being a housewife to Roald Dahl was more difficult than it might have been with other men. I was trying to adapt to the role, but the task was daunting. But I was doing my best that first night Bill came to our apartment for dinner — I cooked, I mixed martinis, and I left the men alone to talk about old times. Or, at least, that’s what they thought.

“Roald had filled me in on who our guest was. Naturally, I was curious what would bring this celebrated and mysterious war hero to our home. I suspected it was more than a social call, or to give his regards to the newlyweds. So I did my best to be unobtrusive, fluttering in and out of the room to check on the dinner, but all the time I was keeping an ear on what the men were discussing. My acting skills evidently paid off, since from what I could tell they spoke openly that night about old times, the war, and those wooden boxes that Bill brought as a wedding present.

“Bill started off with an apology. He said that Roald had been correct back in 1945 — there was a secret that could not be recorded in the history of BSC Roald had been assigned to write. Even in 1953, the higher-ups in London believed the secret too explosive to share publicly. But Bill felt that Roald deserved to know the secret, to understand why he had put Roald in such an uncomfortable position back in 1945. That is where the wooden boxes came in.

“At this point in the evening, Bill handed the biggest wooden box to Roald, wishing him all the best on his marriage. ‘That goes for you also, Pat,’ he said. I poked my head into the room, pretending the sound of my name had drawn my attention.

“ ‘I remember how you always wanted to see one of these,’ Bill said to Roald as he opened the box. ‘It was none too easy to get one. Not too many survived the war, and the ones that did are highly prized. But I still have some connections.’ ”

My eyes were practically burning a hole in that old suitcase Patricia Neal had brought to my apartment. We sat in silence for what felt like an eternity, her sizing me up. Finally, she unzipped the suitcase and lifted out a wooden box. I wanted to reach out and grab it as quickly as possible before she changed her mind, but I restrained myself: it was important for her to give it to me, rather than me taking it from her.

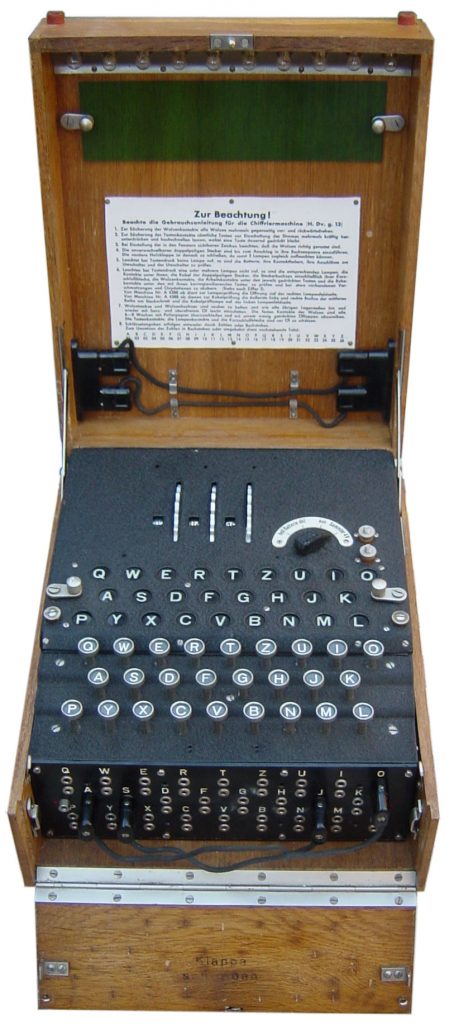

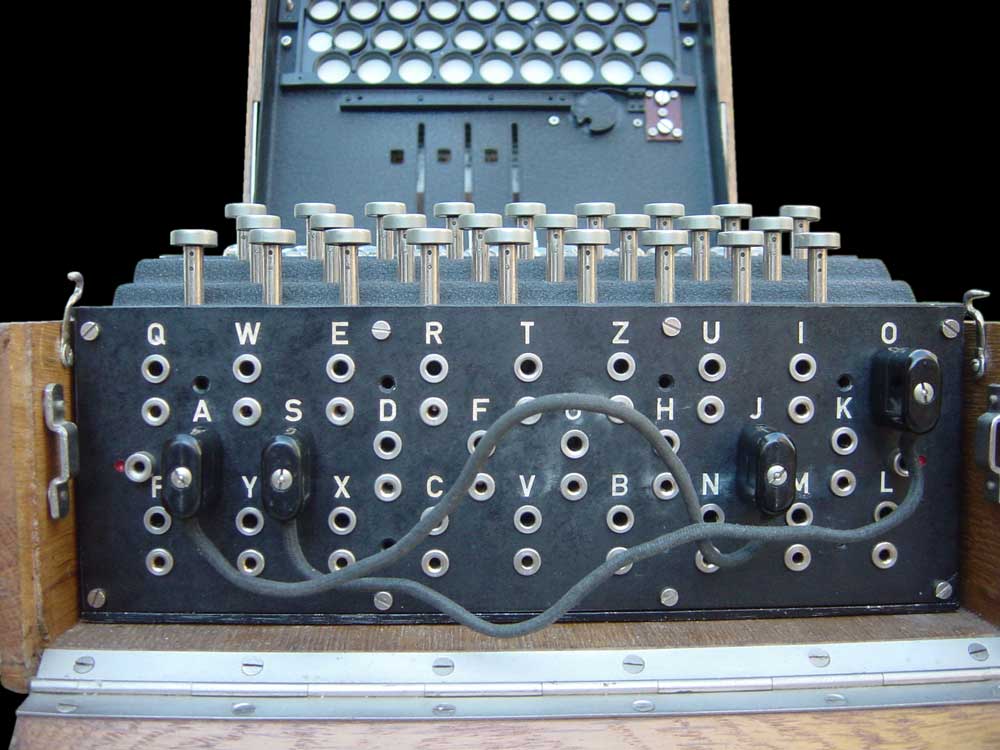

When I finally had the battered box in my hands, I unhooked the metal latch holding the box closed, lifted the cover, and found myself staring at what looked like an old-fashioned typewriter, but with a full set of letters above the keyboard and a space above that with three gears. On the front side of the machine was another set of letters with little holes corresponding to each letter.

~4~

The Enigma machine probably requires no explanation. It may be the most famous device for deciphering encrypted text in history. The German army used Enigma machines to encode messages during World War II. The Germans believed that the messages they sent using Enigma could not be deciphered by the Allies. When the British successfully cracked Enigma, the advantage for the Allies was pivotal.

I later learned that, while William Stephenson and BSC were not directly involved with breaking the Enigma codes, they were deeply interested in the most secure ways to send messages. The need to communicate with Britain and Washington from BSC headquarters in New York was vital to the operation, so much so that Stephenson oversaw the development of BSC’s own enciphering system that was used during World War II and for many years after. BSC’s enciphering systems were never cracked during the war, which is probably why they are less well-known today than Enigma.

William Stephenson, with a contraption that is not an Enigma machine

Ms. Neal continued, “Roald never showed emotion. It was probably his worst quality. But he was awestruck by Bill’s present. I remember it made Bill a little uncomfortable, and he lightened the mood saying, ‘Oh, it wasn’t just for you. I always wanted to see one of these, and this seemed like as good an excuse as any to pull some strings and get ahold of one. I’ve certainly had my fun with it, and I can’t think of anyone who was as obsessed with the Enigma as you. So take good care of it.’ ”

Roald Dahl wasn’t the only one who was awestruck at the opportunity to get his hands on an Enigma machine. I didn’t have as personal an attachment to the Enigma machine as he did, but I was definitely not expecting to have one show up at my apartment. The machine itself was surprisingly well-preserved, considering its age. I wasn’t sure if it still worked. But evidently the years spent in a bank vault had protected it from damage.

“I can see that you are fascinated by this machine,” Ms. Neal said to me as I gently touched its keys.

“Don’t get me wrong, Ms. Neal …”

“Pat.”

I told her I would do my best to call her Pat, even though it didn’t feel right to be so familiar with a woman my grandmother’s age. “Don’t get me wrong, Pat. Seeing an Enigma machine in person is a big kick for me. And having it brought to my apartment by a famous actress is just surreal. But I’m not quite sure what you want from me.”

“David …”

“Mr. Wise,” I corrected her. She was taken aback for a second, until my smile told her I was joking.

“David, the Enigma machine was only part of what was in the safe deposit box. But before I show you the rest, we need to come to an arrangement.”

“What kind of arrangement?”

“You’ll see very soon why I need help. And there are plenty of people who would be more than willing to give me that help — and then proceed to take this machine and the rest of what I’m about to show you away from me. And I don’t want to let that happen.”

“Who are these people?”

“I can see that you think I’m exaggerating the importance of this.”

“I don’t think that at all,” I said. “You walked into my apartment with a rare Enigma machine that must be over 70 years old. If the rest of what you show me is half as impressive, it makes total sense why someone might want to take it from you. I’m just wondering who that might be specifically.”

“The U.S. government, for starters. The CIA. It will all make sense once I show you the rest. But on my terms.”

“What terms?”

“First of all, this all belongs to me. You can’t take it, you can’t Xerox it, you can’t photograph it. And I require total confidentiality. You speak to no one.”

I was starting to see why Pat had come to me, considering my work on the Central Park Papers.

“Are you asking me to do anything illegal?”

“No.”

“Anything that could get me in trouble?”

“Not if you don’t tell anyone about it.”

“Anything that will put me in danger?”

“Again, not if you don’t tell anyone about it.”

That seemed reasonable enough. “I don’t know a whole lot about what you are hiring me for. But as long as that’s all true — that I’m not in danger — and as long as you tell me everything you know, I can accept those terms.”

We then discussed money, the details of which I will omit. Somehow it feels unseemly to discuss our monetary arrangement. I’ll just say that I found her offer more than generous.

~5~

“So what can I do for you? I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you what a historical treasure you have on your hands with this Enigma machine.”

“No. What I need from you involves the rest of Bill’s gift.” Pat reached into the suitcase and pulled out three sheets of old, yellowed paper. “You see, this machine was only part of the wedding present Bill brought that first day he came to our apartment. These papers were the other part.” And with that, Pat resumed telling me about Stephenson’s conversation with Roald back in 1953.

“ ‘An Enigma machine,’ Bill said, ‘would be useless without a message to decipher. On these pages are three actual messages we intercepted. They are not just any three messages. These are the most important messages we decoded during the war. In fact, the war may have ended quite differently if we had not intercepted these messages. The ramifications would have been catastrophic.

“ ‘I know this sounds like hyperbole, but I can’t overstate the importance of these messages. The information in them was the primary reason BSC came to America. Everything else we did, everything you know about what we did, was secondary. It’s still so incendiary that I couldn’t allow any of it to be included in the history of BSC, even after the war ended. I am sorry I couldn’t tell you about this mission at the time, and I respect your not wanting to write the history when you knew it was not complete. Even now, this information is top secret.’

“Roald started to talk, but Bill interrupted. ‘I know what you’re going to ask — if it’s top secret, then why am I telling you now?’

“Bill leaned in and looked Roald straight in the eye. ‘Secrets like this are more dangerous as secrets.

“ ‘Ever since the war ended, I’ve been trying to convince the boys in London that we’d be better off getting this out in the open. I don’t know whether it’s London or Washington that disagrees, but I’ve recently been told in no uncertain terms not to share this with anyone outside BSC. I think that’s foolish, but my hands are tied. But I can tell you, and I feel you deserve to know.’ ”

I’ve presented this as though I am quoting Stephenson. But it is actually what I recall Pat saying she remembered that Stephenson said decades earlier. How accurate is it? I have no idea. But I did see, first-hand, that Enigma machine, and the faded pages on which Stephenson wrote the three messages.

Pat handed me the three pieces of papers. I unfolded the first page.

The page was not what I was expecting. Most of it was taken up by four cryptic sets of verses — riddles, if you will. Each verse had a different heading: Rotor Order, Rotor Setting, Starting Position, and Plugboard Setting. Below the verses, though, was what I was looking for — I saw the words MESSAGE ONE. My eyes darted to the text below.

The message was gibberish.

~6~

I should have suspected as much. Why would Pat have needed my help if it was obvious what the papers said?

Pat’s recollection of what Stephenson said to Roald was this:

“ ‘You deserve to know what happened, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to make it easy for you. And so, in the spirit of Calvert Vaux’s Central Park codes, which you would never stop asking me about, I give you the rest of your wedding present.’ ”

I stopped Pat. “Hold on. They knew about the Central Park Papers?”

“I distinctly remember Bill saying that, because it seemed to come out of left field. It wasn’t until many years later, when I heard about the Central Park Papers, that what Bill said made any sense to me. That’s the main reason I’m sitting in your apartment right now.”

This was a bombshell for me, more than Pat realized. But I had to put it aside for the moment and concentrate on this new case.

Pat continued with Stephenson’s story. “ ‘These messages were not originally enciphered with Enigma, but I have re-encrypted them using this Enigma machine.’ ”

Pat looked at me intently. “So now we get to what I need you for, David. Do you have any idea how to use this machine?”

“I will be honest with you — no. But it can’t be all that hard. As I understand it, the decryption algorithms are complicated, but the actual operation of the Enigma machine is not. It couldn’t be — soldiers in battle had to operate the machines. Plus, we have something they didn’t have: the internet.”

It wasn’t my first time reading up on decryption methods, so it only took about half an hour to learn the basics. The challenge would be simplifying it for Pat, who was surprisingly content to sit patiently at my table while I researched. She got up at one point and looked around my apartment, but I think she was surprised at how little apartment there was to see. First, she examined my bookshelf. Then she freshened up in my bathroom, which I hoped was remotely clean.

When she returned, I looked up from my computer. “Okay, are you ready for your lesson in field decryption?”

“As ready as I’ll ever be,” she said.

~7~

This section is going to get a bit technical. I recommend powering through it, since the information is useful. Alternatively, skip here, where the Enigma settings are boiled down to one easy bolded paragraph. Either way, it may be helpful to revisit this section to really understand how the Enigma machine works.

Here’s how I explained the workings of the Engima machine to Pat:

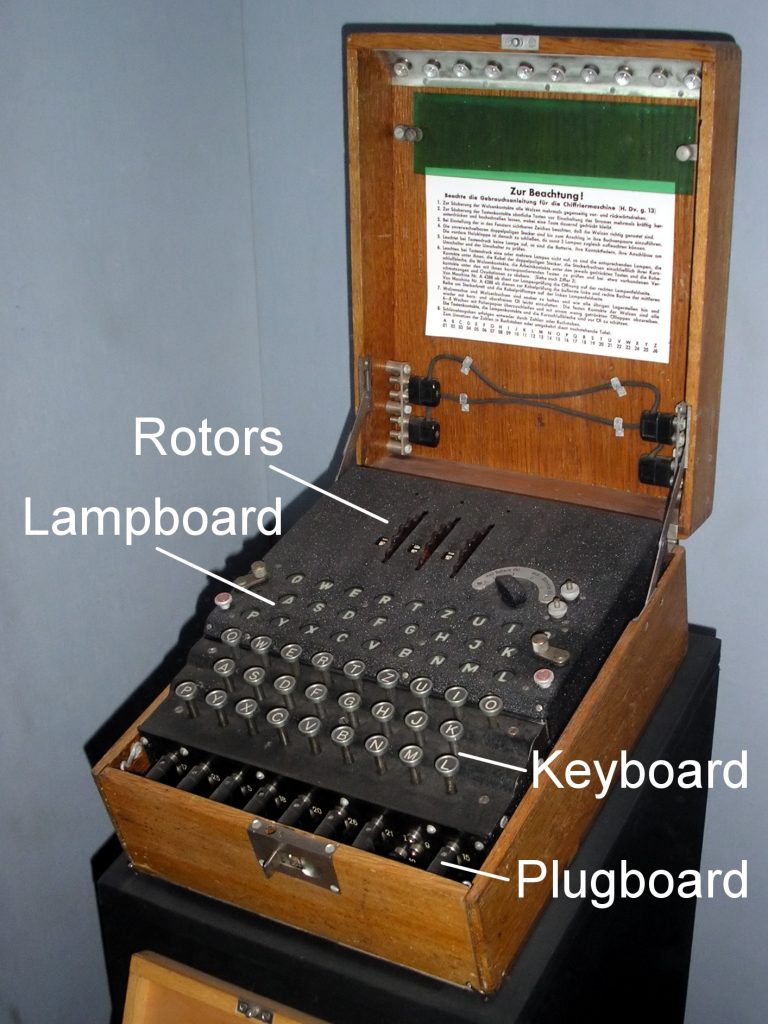

“Not all Enigma machines are the same. This one was known as Enigma I, or the Wehrmacht Enigma, which basically means that it uses one reflector, three rotors, and has a plugboard in the front. Don’t worry, I’m going to explain all of those things to you.

“The Enigma machine, as you can see, is like a giant typewriter.”

“Where does the paper go?”

“There is no paper. Pressing a key makes one of the letters A-Z light up. Except that when you press the letter A, for instance, that’s not the letter that lights up. An electrical current runs from the letter A and lights up a different letter. Now, if it were the same letter that lit up every time you pressed A, Enigma would be easy to crack. But the letter that lights up is always changing.”

“How does it change?” Pat asked.

“First, you can use a different reflector, which alters the path of the current.” I lifted the hinged top of the machine and showed Pat the reflector and rotors underneath.

![By Alessandro Nassiri [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://theatlaspursuit.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Enigma-with-cover-open-939x1024.jpg)

“This big metal cylinder on the left is the reflector. It alters the path of the current so a different letter lights up. In German it’s called the Umkehrwalze. I don’t see any other reflector to change it out with, so I am assuming that we will only need this one marked ‘B.’ ”

“Wait.” Pat said. “There is something else I need to show you.” Pat went into the suitcase and pulled out another smaller wooden box. I recognized it immediately. I had just seen photos of boxes like it online. I opened the box and looked inside.

“These are extra rotors, which we’ll get to in a minute, but I don’t see another reflector. Is there anything else in that suitcase?”

“These.” Pat pulled out a jumble of cables. Why was she giving me each item one at a time? Apparently she still wasn’t sure if she could trust me.

“We’ll get to those cables in a minute also. Okay,” I said as calmly as possible, which was probably not at all, “do you have anything else that might be part of the Enigma machine?”

“No.”

“Are you sure? Because it would really be helpful to see everything at once.”

“There’s nothing else. And watch your tone.”

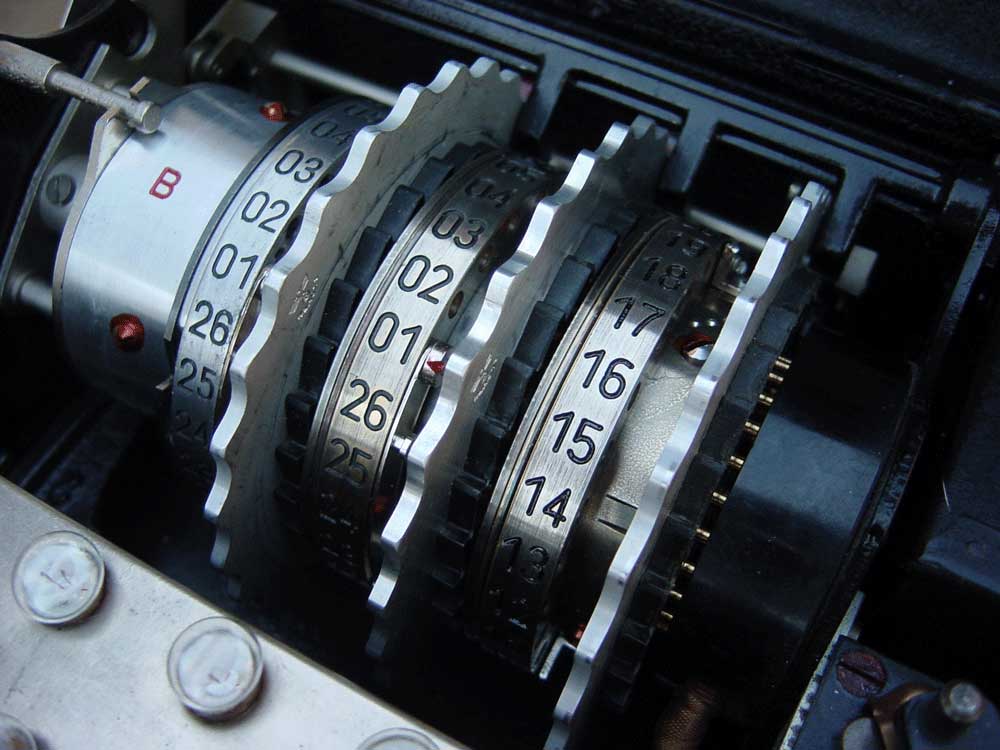

I felt my impatience was justified, but I held my tongue. I just continued showing Pat how the Enigma machine worked, which was a lot easier now that I had all the parts. “Next are the rotors. The rotors also alter the path of the electric current, but they move every time you press a key. That’s why pressing the same key twice won’t make the same letter light up again.” I pulled the three small rotors to the right of the reflector out of the Enigma machine. “See how these rotors are marked with Roman numerals I, II, and III?” I pulled over the smaller wooden box.

![By ArnoldReinhold (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://theatlaspursuit.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/rotor-box-1024x768.jpg)

“There are two other rotors here marked IV and V. You always need to have three out of these five rotors installed, and the order in which they are installed matters. The order is what the Germans called the Walzenlage. It’s a series of Roman numerals that tells which rotors to install and in what order. So, for example, a Walzenlage could be V, I, III, and you would load the rotors into the machine in that order from left to right.”

“I don’t remember seeing the word Walzenlage in Bill’s papers. Is that what Bill would have called it?”

“Good question. I don’t know if Stephenson — sorry, I just can’t call this gigantic figure of world history by his first name.”

“I understand. ‘Bill’ is how Roald talked about him and introduced him to me.”

“In any case, I don’t know if Stephenson would have known the Germans’ terminology or not.”

“Well what does Walzen—”

“Walzenlage.”

“What does Walzenlage mean in English?”

I looked it up. “It means wheel order.”

“Oh,” Pat said as she pulled over the sheet of paper titled MESSAGE ONE. She pointed to the first set of verses. Above the verse was a sub-heading: Rotor Order. “Could that be the same thing as the Walzenlage?”

“I think you’re right. These riddles must be Stephenson’s way of conveying the Enigma settings.”

“Why didn’t Bill do it the same way the Germans did?” Pat asked.

“For one thing, I don’t know if Stephenson would have known at that time exactly how the Germans did it. In any case, it wouldn’t have made sense for him to encode his messages the same way as the Germans. Their system was developed so that encoded messages could be sent wirelessly, and to any of a large number of people. Stephenson was encoding just for one person: Roald Dahl.”

“How can you tell that?”

“Look at these riddles. They are obviously written directly to Roald. Still, maybe you’re right that the basic set-up is the same as the Germans’.”

“I thought you said it was different.”

“My theory is that the way Stephenson conveyed the settings to Roald was different, but that the actual settings themselves are the same.”

Pat’s shoulders slumped. “This is very confusing.”

“Why don’t we take it one step at a time then. First, we’ll master how the Germans used the Enigma machine. Then we will see if we can figure out how Stephenson’s method was similar and different.”

Pat looked worried. “I don’t know if I’m going to be any good at this.”

“I don’t know if I’m going to be any good at it either. But we’ll take it one step at a time.”

“Okay.”

“Good. So we already know that the rotors need to go into the Enigma machine in the correct order. But before you put the rotors in place, you have to make sure they are calibrated correctly.” I picked up a rotor and showed Pat the numbers 1 through 26 in a circle on the inside of the rotor. I pointed out the little arrow on the side of the rotor.

“You move this arrow so that it is pointing to one of the numbers on the rotors. Actually, sometimes the rotors had numbers and sometimes they had letters. The Enigma I was used by the Werhmacht, which was the German army, and it used rotors with numbers 1 through 26. The German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, used an almost identical Enigma machine called the M3. The only difference was that the M3’s rotors had letters A through Z on them. The Enigma I and the M3 are completely interchangeable, since each letter corresponds to a number: A=1, B=2, C=3.”

“That must be what this page says.” Pat was referring to a page in German that was affixed to the inside cover of the Enigma box. It had a row of numbers and letters that looked like this:

“Exactly,” I said. “So the number or letter next to the arrow is what the Germans called the Ringstellung.” I looked at the sheet labeled MESSAGE ONE. “It seems like Stephenson is calling it the Rotor Setting. So a rotor setting of A B C would mean that, before installing the rotors, you would set the first rotor to A, the second to B, and the third to C.”

“Or the first to 1, the second to 2, and the third to 3.”

“You are a natural at this. Then you close the cover. Once the front cover of the Enigma machine is closed, you can see one number — or letter — from each of the three rotors. Then the rotors can be rotated so that any of the numbers 1-26 — or letters A-Z — are visible.

The Germans called this combination the Grundstellung, which they determined and conveyed in a somewhat complicated way using what they called the Kengruppen. Stephenson seems to be calling this the Starting Position. But it also looks like Stephenson’s way is less complicated.”

“How so?”

“Let’s just finish going through the basics, and then we’ll work on how Stephenson seems to be communicating the settings to Roald.”

“Fine,” Pat said, doing her absolute best to follow along.

“The last setting is what the Germans call the Steckerverbindungen, and Stephenson calls the Plugboard Setting. Basically this consists of all 26 letters arranged like a keyboard with holes underneath all of the letters.

Steckerbrett

“This panel is called the Steckerbrett in German. These cables” — I held up the cables Pat had pulled out of the suitcase — “plug into the holes, and can connect any letter to one of the others. All, some, or none of these cables can be used.

“So you can have up to 13 combinations that would be listed as, say, ‘AR TM SK’ and you’d connect one cable between the A and the R, one between the T and the M, and one between the S and the K.”

“That’s simple enough.”

“And that’s it. If you have all of those settings calibrated correctly, and you type in a message that was encoded with a machine set to exactly the same settings, the machine will decipher the message. You just type each letter of encoded text on the keyboard and write down the letter that lights up.”

“What if any of the settings are not exactly right?”

“The machine will spit out gobbledegook.”

~8~

Once we finished the lesson, Pat said, “Now we know how the Germans used this machine, and I think I understand it.” I was impressed with how well she seemed to be following everything. Although she did say, “But I hope you’re not expecting me to do all this myself.”

“Nope,” I said, “That’s what you hired me for. But it’s actually not that complicated. It basically boils down to this —”

I paused. This was important, and even though I was going to guide her through it, I wanted her to understand it. That’s why I’m bolding this paragraph:

“— All you need to know is that we’re using an Enigma I, which is the same as the M3. The reflector doesn’t change — it’s always B. For the Rotor Order, you need three of the Roman Numerals I-V, and none of them can be repeated. For the Rotor Setting and the Starting Position, you need three numbers 1-26, or three letters A-Z. For the Plugboard Setting, you need up to 13 groups of two letters each, and none of the letters can be repeated.”

I thought that was clear enough, and Pat seemed to agree.

“So how did Bill’s method differ from the Germans’ method?”

“That’s the question. It certainly would have been easier for us if Stephenson had encoded the messages he gave Roald the same way the Germans encoded their messages. It’s now public knowledge how the Germans made sure the Enigma operators used the same settings. A codebook was distributed each month with the settings for each day of that month.”

“So where is the codebook?” Pat asked.

“I think these riddles are the codebook.”

“A bunch of riddles are the codebook? That’s the least German thing I’ve ever heard.”

I laughed. “Well, Stephenson wasn’t German.”

“True. But I don’t think he was a riddle writer either.”

“Maybe not. But Roald was.”

“That’s for sure. Roald loved riddles and poems and ballads. His children’s books are filled with songs and poems.”

“So maybe the riddles were for Roald’s benefit.”

“But if Bill wrote the riddles for Roald, how are we going to figure them out?”

I tried to reassure her. “I hear what you’re saying. When I first looked at the clues Stephenson gave Roald, I thought I’d never be able to decipher them, because they were written specifically for Roald. But we have a few tricks up our sleeve that Stephenson could never have anticipated.”

“What tricks?”

“The internet, for starters.”

“And what else?”

“Our secret weapon. You.”

“Me?”

“You were Roald’s wife, so I have a feeling you can help with anything I can’t figure out.”

“I’ll do my best.” Pat replied. “So, does this Enigma machine even work?” Pat asked.

I looked at her incredulously. “You mean you haven’t tried the machine out?”

“I didn’t know how to use it, and I didn’t want to break it.”

“You won’t break it,” I assured her. “Go ahead. Touch one of the keys.”

I wish I could report that the Enigma machine in my apartment sprang to life and began working when Pat hit that first key. But while 50 years in a bank vault had kept the machine in tip-top shape, the battery was dead.

“Now what are we going to do? I don’t suppose you have a replacement battery for an Enigma machine lying around your apartment?” Pat asked.

“Unfortunately, no.” I replied. “But the fact is we don’t really need this machine to work at all. Much as I would like to do this the old-fashioned way, there are plenty of online Enigma simulators that will work just as well. All I really need is a copy of the coded messages and the clues.”

I took a few minutes to copy them down. When I was done, I looked up at Pat and said, “Alright, I think I have everything I need. Is there anything else you have to tell me?”

“I think I’ve told you everything.”

“Great. Then I’ll get to work on cracking these messages. If I have any questions I’ll be in touch. Otherwise, I’ll let you know once I decipher them. What’s the best way for me to contact you?”

“I don’t think you understand, David. I’m not looking for you to get back to me in a few days or weeks. I need to get to the bottom of this now.”

That was a surprise. “What’s the hurry? This has been sitting in a bank vault for decades.”

Pat sighed. Apparently there was, again, something she hadn’t told me.

“David, you were not the first person I called after I emptied the safe deposit box. Once I realized what was in it, and that I wouldn’t be able to decipher the messages without help, I thought long and hard about who to contact. I wanted to be as discreet as possible, since I knew that whatever this involved, it was top secret. That much I distinctly remembered from when Bill came to the apartment. So I considered entrusting all of this to someone completely unconnected to the government, like you. But an old friend of mine has a son who works in the Intelligence Department, and in the end I decided to call him. His name is Jack Lester. I figured Jack would know how to help me. I finally called him last night, told him about what I had, and asked him not to take this up the Intelligence flagpole until we knew more about what specifically it involved. Jack lives in Washington D.C., so this was all over the phone.

“There was something about that phone call with Jack that made me uncomfortable, and I was taken off-guard when he said that he would drive up to see me this morning. I started to wonder if calling him had been a mistake. I tried to put him off for a few days, but he kept insisting. I can’t quite put my finger on exactly why, but I started thinking that maybe someone in the government was exactly the wrong person to contact.

“Still, what’s done was done, and I figured I had to just trust Jack. After all, I’ve known him since he was born. He visited us when he was a little boy. He used to run around that same apartment where Roald and I hosted Bill right after we were married.

“Then this morning, I realized that I didn’t have any copies of the papers from the bank vault. I certainly wasn’t going to give Jack the originals. I wasn’t even sure I should give him copies, but I figured I should have some ready. So I packed everything into this suitcase and went to go make copies at a store down the street.

“When I got back to my building, there were three very official-looking cars outside, and Jack was at the front door trying to get in. David, six men in uniform were with him. At that point I really regretted having called Jack. I had specifically asked him not to tell anyone about this, and he had done just that. Jack didn’t see me. So instead of going in, I went around the corner and went into an absolute panic about what to do.

“Then I remembered about you, and Bill’s cryptic reference to Calvert Vaux’s Central Park codes. My neighbor always tells me about all sorts of crazy things he’s read or done. Normally, it barely registers. But a few years ago he told me how fascinated he was with the Central Park Papers. I thought to myself maybe that had to do with what Bill said that night in our apartment. I asked my neighbor for more information and he printed out a sheet of paper with your phone number. I put that paper with everything I had taken from the bank vault. So, as luck would have it, I had your phone number with me when I went out to make copies. I called you, and came straight here.

“I assume it won’t be long before Jack and those men discover that I’m gone and I’ve taken everything with me. I need to get to the bottom of all of this before they find me.

“Also, once bitten twice shy, so I am not going to be leaving anything with you. We’re going to have to figure this all out together.”

“Looks like I’ve got myself a partner.”

Pat nodded.

Then I said, “So when I asked if you’d be wanting me to do anything dangerous, and you said no, that was not really accurate, was it?”

“I said it wouldn’t be dangerous as long as you didn’t tell anybody. If no one knows you’re helping me, then you’re not in any danger.”

That didn’t exactly put my mind at ease. I wondered if I really knew what I was getting myself into. I had been so focused on convincing Pat that she could trust me. I never considered whether I could trust her.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that Pat’s life might be in danger. And now, so might mine.

But it was too late to turn back. If this involved something top secret that the government was anxious to keep under wraps, I already knew too much. Despite the danger, my only option was to figure out what this was all about.

I turned my attention back to the page of Stephenson’s papers with the heading MESSAGE ONE. I scanned down the page and quickly came to a realization. “We’re not going to figure this out sitting in my apartment. Stephenson obviously expected Roald to go to specific places in order to decipher these clues. I hope the places still exist.”

“I hope there aren’t too many stairs. Are you sure we can’t figure this all out on your computer?” Pat asked.

“I expect the internet will be extremely helpful. And maybe it’s possible that a cracker-jack internet sleuth could figure this all out in front of a computer screen. But just reading over these first clues, I think it will be best and easiest to just go where Stephenson’s clues take us.”

“I suppose you’re right,” Pat said, though the look on her face showed she was nervous.

“We’ll walk slowly,” I said, “And I’ll do my best to help you. I just have no idea how far we’ll have to travel. I don’t even know if the places are in New York.”

“I can tell you for sure that the first one is,” Pat said.

“How do you know that?”

“Because I think it’s referring to me.”

I re-read the clue and realized she was right. “So you know where we need to go?” I asked her.

“Of course,” Pat replied. “Shall we go?”

She closed up the Enigma machine, put it in the suitcase, and headed for my front door.

I said to her, “You realize we don’t need the Enigma machine with us. It’s awfully heavy, and we’ll have my phone and computer for all of our deciphering needs.”

“And what would you suggest? That I leave the Enigma machine here in your apartment?”

“That is not an option for you?”

“David, I’m not letting this machine out of my sight.”

I thought it best not to argue with her. I just said, “Got it. Let’s go.” And off we went.

~10~

I’m not going to reveal the decoded text of the first message. Stephenson didn’t make it easy for Roald, and neither of them made it easy for Pat and me. It’s far more fun and rewarding to figure it out for yourself.

Below is a recreation of the page that Stephenson gave to Roald, complete with the encoded first message and the clues Stephenson gave Roald to decipher the message.

I will give you a few advantages. First, just in case you don’t have an Enigma machine lying around, you can use an Enigma simulator to decode the message. Here is a link to an Enigma simulator I created. Truth be told, I didn’t create it from scratch — I just adapted it from a freeware simulator created by Daniel Palloks (who I don’t know). My version is easier for novices, English speakers, and mobile users who are reading The Atlas Pursuit. You don’t have to use mine — there are plenty of websites with Enigma simulators. Some that I have found particularly helpful are detailed here. But I think you’ll find mine more user-friendly.

Second, I’ll give you a little advice:

~ Keep in mind what a potential solution to each clue could be. This page has that information summarized, or you can go back and read it in my discussion with Pat.

~ Bring an internet-connected device with you — a smartphone at least, a tablet or laptop even better.

~ Pen and paper come in handy also.

If you need more help, go to the Help page.

I have encrypted the rest of my description of my time with Pat, including the second and third messages and clues to decipher them. I have not used the Enigma to encipher these — they are far too long to use Enigma. Instead, I’ve used a modern-day password protection. The password is very simple — it is the first and last word of the decoded text of Message One, all lower-case, no spaces.

MESSAGE ONE

Rotor Order

From chapters on the portals where

The bride and groom were wed

Use three that match the rotors in

The order they’d be read.

Rotor Setting

Two hundred steps away there kneels

A man in solemn prayer.

His age would have been this when first

He started praying there.

Starting Position

Above his head and to the east

Adjacent to the hall

These last three letters there adorn

The western-facing wall.

Plugboard Setting

That pilots all were born to fly

So mischievously quoth

These devils that you wrote about

Who almost killed us both.

Message One

JITIQ GUFPG OONEB WLOJI XTZTY NPASI GKXGX PIDRU XLDQQ CTDIM VNDKE RKEKV HWMDP CDMYM UISCS BXA

The password to open Part II of The Atlas Pursuit is the decoded first and last words of Message One, all in lower-case and without a space between the words.